Books and articles about lean manufacturing the term U-Shape Cell (U-shaped or horseshoe-shaped production cell) flashes quite often. Frequent mention may suggest that this way of organizing the process is the best in terms of Lean. Is it so?

The U-shaped cell, under certain conditions, may be the optimal production method. Profitable hallmarks such a line could be:

- low level of work in progress (WIP);

- single piece flow;

- flexible capacity planning and the number of operators involved;

- convenient supply (presentation) of the material

- etc.

However, U-Shape is not the only way to organize production and is not always the best way to arrange workstations (equipment, machines, etc.). For example, arranging tables in a “U” shape in a call center will not speed up work or reduce customer waiting times.

So what is the most lean way to organize production?

There are several basic ways to organize production process:

- Production in batches and queues: a process consisting of sequential operations, between which work in progress accumulates (WIP 1). The amount of work in progress is at best equal to the size of the batch that moves from operation to operation.

- Line (or cell) production: a process consisting of interconnected operations, the material between which moves piece by piece or in small controlled batches. Important feature of this process is that the amount of work in progress is strictly limited.

- One-stop production: one universal machine(like a “pit” for an auto mechanic) or the so-called.

Point 2 - production in a line (or cell) - implies many configuration options. Here are the most common ones:

- straight line (I-shaped cell);

- horseshoe line (U-shaped cell);

- T or Y-line;

- C or L-shaped line.

As mentioned above, option 2b is mentioned most often in books on lean manufacturing, however, as you can see, it is not the only one possible:

In addition, the entire production cycle can consist of several sections, each of which can implement a different production method or a different type of line (cell). For example, at McDonalds, you can watch the checkout - D-shop - and guess that something like work is going on in the kitchen in the cells, the configuration of which depends on the layout of the kitchen. It connects the kitchen and the checkout in a kind of supermarket:

How to choose the best option for organizing the production process in the conditions of your enterprise?

Under the organization of the production process, we mean the organization of everything that is between the warehouse of raw materials and the warehouse finished products. In a simplified version, this is the flow of material from one warehouse to another. The organization of such a flow means the elimination of the maximum number of obstacles on the way. In lean manufacturing, these obstacles are called waste.

The goal of eliminating waste (obstacles to the flow) is to speed up the flow of materials. Thus, as a result of eliminating losses, the material should “flow” along the shortest trajectory, without encountering obstacles on the way (read, without stopping).

What is the shortest material flow path in your facility?

If, for example, at your enterprise, the warehouse of raw materials and finished products are separated - located at different ends of the building - then the shortest trajectory will go in a straight line:

The ideal material flow path in this case would be a straight line. This is how many automobile factories work: on the one hand, bodies are brought in; on the other, finished cars are moving out. This is how a lot of Cross-Docking warehouses (ports, auto and railway stations) work: on the one hand, containers are unloaded, and on the other hand, they are loaded onto the next transport. Even your favorite supermarket can be divided into two areas: a warehouse and a trading floor. On the one hand, from the side of the warehouse, they unload products, and on the other, from the side of the trading floor, they let visitors in.

If the warehouse of raw materials and finished products are located on the same side of the production site, then the shortest trajectory of the flow of materials will resemble a horseshoe:

Of course, you can say that both methods are not applicable in the conditions of your enterprise. For example, the first one is not suitable for you, since the distance between warehouses significantly exceeds the length of the production line. And the second one is not suitable because your company has more than one line.

Reasons why not? there is a mass. However, it is important that in your search for the most lean way of organizing production, you first choose a method - a concept, and not immerse yourself in details. Often we tend to go into the elaboration of details. Every detail requires careful weighing and thought, and I assure you, this road leads nowhere.

Solve the problem conceptually - choose a method, and only then work out the details and solve problems as needed. Often, a lot of unsolvable elements will subsequently not require any solution from you at all, or the solution will be known. In other words, determine how the material should move, and then think about how to “fit” individual operations, cells or D-shops into this flow:

And if you need to reorganize the warehouse a little, then why not?

Of course, the choice of a conceptual solution for the movement of material through the production area does not mean that you have achieved an optimal production process. But a start has been made, and the first step has been taken correctly. And this is the main thing!

Based on Cellular Manufacturing with Kanbans Optimization in Bosch Production System, Pedro Salgado, Leonilde R. Varela, 2010

A study of existing production practices has identified a number of bottlenecks that need to be addressed. First, excessive costs - in particular, the purchase of twelve laser machines for printing codes on circuit boards. Second, the current manufacturing system lacks flexibility—it has proven unable to quickly adapt to changes in demand, requiring corresponding changes in product design and process requirements. Thirdly, equipment downtime is not uncommon, since the failure of one machine can often bring the whole machine to a halt. production cycle.

This article proposes to modify the production system through the creation of production cells, which will allow production operations to be performed in a clear sequence without interruptions due to the layout various types equipment in one area. In the case of Bosch Car Multimedia Portugal, S.A. redistribution of equipment reduces the number of lines from twelve to seven, thus reducing the number of required laser systems. With three machines already in production, the company only needs to purchase four new ones in addition to the existing ones to completely solve the problem of labeling boards in the automated assembly area. Such a decision will allow the company to save a significant amount.

The proposed scenario includes the establishment of Just-In-Time Cells (JITC) and Quick Response Cells (QRC). The former follow the principles of JIT in everything, aim to achieve the same key goals (zero defects, zero installation time, zero inventory, zero unnecessary manipulations, zero equipment breakdowns) and use unified kanban containers. The latter allow you to significantly reduce inventory, since the stock that ensures the continuity of the production process between regular deliveries, does not exceed the amount consumed during the time during which the order is placed and executed.

Just-in-time logistics is increasingly being used in cell organization as it makes the manufacturing system more flexible and adaptable to changes in the production of product families, which is essential in today's economic environment. competitive advantage. This factor is of great importance for the Bosch Production System, since the boards produced belong to the same product family and therefore share certain characteristics in terms of production and handling requirements, including similarities in design and materials.

When Bosch was faced with the need to meet a wider range of product specification requirements, management came to understand how important it is today to be able to quickly adapt a production system and key processes, and it was flexibility and responsiveness that became the most important characteristics production cells. In addition, cell production enables higher product quality levels to be achieved while maintaining process efficiency at high level and minimization of inventory and movement of goods, materials and employees in the course of work. On fig. 1 shows the recommended cell layout.

Such work environment It has a number of advantages in customer relations as well, since the production cells are focused on fast production rates, allowing to satisfy the customer's requirements in the shortest possible time.

Domestic deliveries are planned to be organized according to the principle of a milkman. When picking up the container from storage in the automatic assembly area, the final assembly work areas leave the empty container in place of the full one. This signals the beginning of a new cycle, and as soon as the container of materials leaves for the final assembly area, the kanban cards are returned to the board.

Accordingly, when there is a need for materials in the automatic assembly area, workers pick up a full container from the supermarket - a storage point for the minimum required stock. Whenever a kanban card is returned to the board, it serves as a signal to create a new batch of product. When the required production volume is reached, the cards are placed in a buffer, from where they exit on a FIFO (first in, first out) basis.

From the buffer, the cards are sent to the planning sector, located at the very bottom of the board. Here, based on the data presented on the cards, production planning for three working periods. The cards then pass through the entire line, are attached to a container and sent to the supermarket, where the materials are stored until they are needed in the automatic or manual assembly area.

For a more visual comparison of the existing and alternative scenarios, we use the already analyzed example with the production of boards (Fig. 2) and the same calculation formula:

In the proposed scenario, only the effective production time (NPT) and the replenishment time (RT loop) differ. This is due to the fact that production in cells allows you to reduce the time of preparation and changeover of equipment and the duration of processing. Thus, the effective production time is increased, the product processing time (25 minutes) and the cycle time (9 seconds) are reduced.

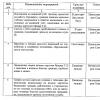

Tab. 1. Calculation of production parameters under an alternative scenario

|

Product Type I |

PR - demand per unit of time [units/time];

SNP - standard number of parts in a kanban container;

WA - volume of selected products [units/time];

NPT - effective production time [min./period];

RT loop - production replenishment time [min.];

LS - lot size [units];

ST - "safety" time (hours).

With these values, we can calculate the cumulative replenishment time (RE), cumulative lot volume (LO), cumulative pickup peak (WI), cumulative downtime (TI), cumulative safety time (SA) respectively - see .table 2.

Tab. 2. Calculation of production parameters under an alternative scenario

|

Product Type I |

RE - cumulative replenishment time;

LO is the total volume of the lot;

WI - cumulative peak of "fence" of production;

TI - cumulative downtime;

SA - cumulative "safety" time;

As it follows from the calculations, the organization of production cells allows you to reduce the number of kanban containers from 35 to 30. Given the pace of production, this means a saving of 5 containers per day, 100 per month (with 20 working days) with full satisfaction of the entire volume of demand. Thus, in half a year we will save 600 containers, which is a very significant indicator.

The reduction in the number of containers is due to an increase in effective production time, on the one hand, and a reduction in replenishment time, on the other.

Taiichi Ohno noted that reducing the number of kanban containers reduces the amount of intermediate and final inventory, allowing the company to better adapt to fluctuations in demand. And Shigeo Shingo also found that eliminating excess inventory can cut labor costs by 40%.

Based on the available product and demand data, a forecast was made of the need for the company's products six months ahead for an alternative production scenario (Fig. 3).

According to estimates, by the end of the allocated period, the number of containers will be 2581.

By comparing the results of the calculations, we find that when we move to production cells, we will significantly reduce the total number of kanban containers. For half a year of work, instead of 2936 containers under the existing scenario, we will get 2581 containers (355 less). Thus, the savings for six months will be 12%.

Demand is expected to fluctuate throughout the months. At the moment of increasing demand, the number of containers will increase accordingly to meet the needs of customers and vice versa. Taiichi Ohno has shown from experience that fluctuations between 10% and 30% can be easily managed without increasing the number of containers. However, it is worth remembering that the most reliable indicator is practice - each company has its own strategy for responding to changes in demand.

On the other hand, according to J.T. Black, the main advantage of cell production is not even in reducing the number of kanban containers in production chain, but in increasing the flexibility of production, in its increased ability to quickly respond to changes caused by both external factors (most often changes in demand) and internal factors (regarding changes in product design or expansion of the production line).

The efficiency advantages of production cells over traditional production models have been widely discussed by Roger Eskin and Nanua Singh. The benefits have been established as a result of simulation modeling, analytical studies, practical implementation and are summarized as follows:

- Reducing changeover times. The production cell is organized to handle parts of similar shape and size, so similar fixtures can be used to hold them. Common fixtures can be developed for a family of products, greatly reducing the time needed to change fixtures or tools.

- Batch size reduction. By reducing changeover times, it becomes possible to use smaller lot sizes, resulting in a more consistent production process and lower costs.

- Stock reduction finished products and in-process products through smaller lot sizes and reduced setup times. Eskin pointed to the possibility of reducing products in the process by 50% with a 50% reduction in changeover time. In addition, the volumes of stored finished products are significantly reduced, since smaller batches are made instead of stock production and on a just-in-time basis.

- Reduced lead time- by reducing the changeover time and the time spent on operations with raw materials.

- Reducing individual tooling requirements. Parts are produced in cells and have a similar shape, size and structure. Often they have similar requirements.

- Reduced overall lead time. In a traditional manufacturing system, parts are moved between stages of the manufacturing process in batches. In the cells, the finished part immediately goes to the next stage of processing, which can significantly reduce the waiting time.

As a result of the aforementioned factors, the quality of the products also increases, because due to the fact that each part is transported from one stage to another individually, the Feedback, and the process can be stopped immediately when a defect is detected.

Summing up the analysis of the existing logistics system at Bosch Car Multimedia Portugal, S.A. and the alternative proposed to it, we can conclude that the transition to production cells can significantly reduce the costs of the enterprise, improve its production system and management production tasks. In addition, this is a step towards simplifying the handling of materials.

In conclusion, I would like to note that it is possible to achieve the results recorded here by simply changing the production layout and creating cells. By improving some other aspects - such as production planning, inventory flow, management control, etc. - even more outstanding results can be achieved.

Given the heterogeneity of automated means of production, it is necessary to clarify the basic concepts, terms and definitions used in mechanical engineering industrial production. The terminology according to GOST 26228-84 is taken as a basis.

Production- a complex of coordinated work processes in which the conscious targeted activity of people is aimed at creating wealth(products, services) or information flows to meet the relevant needs of society.

System- a collection of material or virtual (scheme, mathematical model) objects identified taking into account the properties and features that distinguish this system from all other systems. From this point of view, a system can be understood as any technical object in which the connections between input and output parameters are distinguished, even without considering the physical or other phenomena that occur during the operation of the object and determine the conditions for this operation. Typical example this approach - cutting systems.

Production system (PS)- a static or dynamic combination of human, material and financial resources, which ensures the transformation of actions at the entrance to the system (personnel work, objects and tools, information) into results at the exit from the system (industrial products, materialized services, new information).

Manufacturing- part of the production process, during the implementation of which, with the help of means of production, manufacturing technologies, raw materials and semi-finished products are converted into new industrial products.

Technological system (TS)- a set of functionally related means of technological equipment, items manufacturedmanagement, finance and performers, designed to perform a particular technological process or operation. So, for example, a machine tool can serve to process a specific surface of a part or, as one of many subsystems, be included in a common system for processing a part, and later on, assembling a machine.

Technical system- a complex that performs specific functions in technological system. The name of such systems is determined by their purpose. For example, in metal cutting machine it can be hydraulic system, control system, supervision and diagnostic system, etc.

System Structure—- a set of spatio-temporal connections between the elements of the system.

Subsystem is a system of the lowest level, singled out in a complex system.

Production automation- usage technical means For automatic control and control of production processes. At the same time, unlike mechanization, which is aimed at facilitating the physical labor of an employee, automation is aimed at reducing (eliminating) the direct participation of a person in the production process and orienting him to programming and general supervision of the process. Automation can cover the means of production ( technological machines), individual components of manufacturing processes (manipulation of objects, their transportation, storage, control), as well as the entire manufacturing process (complex automation).

Flexible factory automation (FAP)- automation that provides quick and easy re-equipment (changeover) and change of the program of work of production facilities in accordance with changes in production requirements. Such automation is the opposite of rigid automation, designed to produce only one type of product, the transformation of which requires a very significant investment of time, labor and financial resources.

Flexible Manufacturing Module (FPM)- unit technological equipment, which automatically performs technological operations within its technological characteristics, able to work autonomously and as part of flexible production systems or cells. The GPM includes devices: CNC, adaptive control, control and measurement, diagnostics.

Flexible production cell (FFC)- a set of several GPMs controlled by computer technologyand systems for ensuring functioning, capable of operating autonomously and as part of a flexible production system in the manufacture of products within the prepared stock of workpieces and tools. The system for ensuring the functioning of the GPO includes automated system process control, automated process equipment control system, automated

By definition, a production cell is the arrangement of equipment and workplaces in such a sequence as to ensure the rhythm of materials, components and other components in the production process with minimal, in particular, delays in their transportation.

We can say that the alignment of the cell is the arrangement of machines in accordance with the sequence of operations, when medium-sized and inexpensive equipment is allocated exclusively for any particular product.

Based on the foregoing, the production cell requires a combination of professions, because a worker or several in a cell must be able to work on different types of equipment (possibly all) that make up the cell. It is necessary to define and clearly prescribe, plan the number and frequency of movement.

According to the types of construction, there are L-shaped, T-shaped, V-shaped, I-shaped and others, depending on the technology, the layout of the site of their location and other factors. The most popular are U-shaped production cells.

In any case, the layout of the cell must be organized in such a way that equipment, tools, materials, standards are at hand, and their location ensures the safe performance of work.

Algorithm for the formation of a production cell quite simple (see figure).

To get started, you need to assortment selection. Despite the similarity with, here the emphasis is not on goals, but on the mass character of the product, since the formation of a cell involves a physical change in a certain area (moving jobs and equipment). This should be the most massive nomenclature, selected according to the principles of ABC analysis and visualized using d. Pareto, covering the largest number flow operations, i.e. with the longest technological chain. If you are already at the stage of choosing a product for considering such a product, then you are on the right track. Otherwise, consideration should be given to organizing the cell in light of a different set of different product ranges.

Do the capacities allow and is it advisable to form a cell?

Is it possible to form a production cell on another item or on several types at once?

After choosing an assortment, a current state plan, which consists of a layout of the site indicating the technological equipment, a diagram of the movements of the worker in the process of converting the selected product, and possible necessary instructions, for example, quality control, the need for a special skill, Special attention safety precautions, etc. Making a plan allows us to understand the current state, see and start generating ideas for improvement. Here it is also necessary to carry out the execution of each operation (on the corresponding piece of equipment) according to the Spaghetti diagram, i.e. indicate the time spent on each action of the workers.

As a rule, the current state reflects technological sequence transformation of any product, passing through several types of equipment and several operators, i.e. operations, at the input and output of which there is a certain amount of work in progress. Timing data is needed to plot the chart and equipment grouped into a cell under the required. Balancing under is the next step in cell formation. Here you can take advantage not only of the redistribution of actions and elimination, but also experiment with different options for the location and amount of equipment. Operations that for some reason cannot be balanced are not included in the cell.

Based on balancing results, required takt time and equipment relocation capabilities the plan of the production cell of the target state is formed, i.e. as we want. The plan includes a diagram with the required arrangement of equipment in the form of a cell and the minimum number of workers, as well as a summary table containing a list of actions performed in the production cell, broken down into automatic operation of the equipment and the direct actions of the worker himself (including movement, removal and installation of products, etc.). More clearly the summary table of standardized work in the form of a cyclogram.

For example, when organizing a cell for a bicycle assembly operation, if you know the sequence and duration of each operation, as well as the required one, the table of standardized work may look like this (see table):

Data for calculation:

| № |

the name of the operation |

Duration, sec |

|

Rear wheel installation |

||

|

Installing the front wheel |

||

|

Handlebar subassembly |

||

|

Steering wheel installation |

||

|

Seat subassembly |

||

|

Seat installation |

||

|

Suspension subassembly |

||

|

Running gear installation |

||

|

Wing installation |

||

|

Package |

Total time = 2190 seconds without taking into account the movements of workers. In this case, we deliberately simplify the example by rounding up the execution time of each operation to whole minutes, thereby taking into account the movement of the product and possible losses.

In the above example, the operation of the cell was calculated for a cycle of 600 seconds (10 minutes).

Thus, it took 2190/600=4 assembler operators to perform work to the beat.

In domestic and foreign historiography, for a long time, the latifundia was considered the main type of economy in antiquity, which was depicted as a huge estate with hundreds and thousands of slaves, mostly convicts, with a pronounced subsistence economy and minimal ties with the market. It was this type of economy, scientists believed, that best of all reflected the most significant aspects of ancient production and society (V.S. Sergeev, S.I. Kovalev, N.A. Mashkin).

However, since the mid-60s, a different point of view on the nature of the main production unit in Roman agriculture has been established in Soviet antiquity (M.E. Sergeenko, E.M. Shtaerman). Modern Analysis historical material showed that the latifundia in the above form in the classical period (until the end of the 1st century AD) was not the dominant economic type. The most common and accumulating the main principles of developed slavery production unit was a medium-sized estate serviced by slave labor and closely connected with the local market (commodity slave villa). Recognition of this fact led to a significant rethinking of the whole character of the Roman Agriculture, the entire Roman economy, especially the role of commodity production in it, in comparison with the previous concept, which was based on the economic type of a huge latifundia with natural production ...

Agricultural Italy lagged behind in the formation of a new economic type both from the Balkans and from Great Greece. Up to the III century. BC. in Italy, including the Etruscan urban centers, the dominant type of economy was the peasant allotment, where the owner himself, a stern and pious Roman, and his entire large family worked hard. Various data allow us to determine the size of such an allotment: it hardly exceeded 20-30 yugers (5-7.5 hectares) ... In early Rome, large land ownership in its structure was not so much a single centralized production, but a collection of plots dependent on the owner, which was a certain part of the harvest. The harsh debt law, the dependent position of the plebeians, the traditional custom of the clientele created favorable opportunities for the existence of such a structure. The Roman vocabulary did not even have the term villa itself and the concept associated with it. In any case, it is not in the laws of the XII tables. It most likely appeared in the 4th century. BC. in connection with the legislation of Licinia-Sextia (367 BC), which approved large land ownership and defined land ownership of 500 yugers as private property, which is at the complete disposal of the owner.

In essence, the legislation of Licinius-Sextius established the guarantees of large land ownership, created the conditions for its formation and distribution. Another such condition appeared after the abolition of debt slavery in 326 BC. among Roman citizens, which reduced to a minimum the sources that fed the archaic structure of large land ownership, and oriented the owners of large estates (up to 500 yugers) to the use of the labor force of slaves obtained from sources external to the civil collective.

The implementation of these conditions in everyday life contributed to the intensive urbanization of Italy in the II-I centuries. BC, the transformation of patriarchal Italian towns into large craft centers with a large population and the active aggressive policy of the Romans, accompanied by mass enslavement. The general development of agrarian relations in Italy IV-II centuries. BC. followed the same path that the Greek policies had already passed in the 6th-4th centuries. BC, only the scope and depth of this development in Rome were an order of magnitude greater than in the Greek world. One of its results was the design, introduction and wide distribution of a new economic type in agriculture, namely the commodity slave estate. In principle, this was not a new type for ancient society, its main features matured and were embodied in the estates of Iskhomachus, the estates of southern Attica and Chersonese Tauride, the estates of the Sicilian slave owners of the III-II centuries. BC. However, it was under Roman conditions that the commodity slave-owning estate took on a finished form, formed its complete structure, revealed all the internal possibilities inherent in it, i.e. became a clearly defined economic type, most adequately expressing the deep features, the essence of classical slavery.

When developing the structure of a commodity slave-owning estate, the Romans made full use of the Greek experience in the functioning of similar farms. In the plays of Plautus, the slave-owning estate with a villa in the center is seen as a natural and habitual phenomenon. The data of Cato's treatise "On Agriculture", written at the beginning of the 2nd century BC, are more definite. BC. In this work, the phenomenon of a commodity slave-owning estate is developed with such completeness that subsequent agrarian writers (Varro, Columella, etc.) supplemented rather than reworked Cato's model) ...

Estate of the Catonian type in the 1st century. BC. from Campania and Latium is widely distributed throughout all regions of Italy, including Cisalpine Gaul and Sicily. This all-Italian experience of the operation of commercial villas was theoretically summarized in Varro's essay On Agriculture. In the 1st century AD this type of production cell began to take root in the agriculture of the Roman provinces, being the most important element of Romanization, a reflection and embodiment of the classical slavery of the Roman type. Archaeological excavations have uncovered several hundred villas of this (or close to it) type in almost all Roman provinces. Naturally, in the process of its spread, the commodity slave estate was not introduced mechanically, but was influenced by the local environment, local traditions, and local forms of agricultural organization. Therefore, it would be more fair to call this type, if we mean certain provinces, not Roman, but Roman-Spanish, Roman-Gallic, Roman-African, Roman-Egyptian, etc. However, with all the differences, these were variations within the same economic type.

A theoretical generalization of the general imperial experience of the functioning of such estates, the level of agricultural technology and profitability, and the organization of the labor force was given by Columella in his agricultural encyclopedia and by Pliny the Elder in the botanical books (XIV-XIX) of the monumental work "Natural History". A detailed development of the legal foundations for the existence of a slave-owning estate was carried out by Roman lawyers and preserved in the Digests ... This eloquently indicates the wide prevalence (of this type of economy), deep penetration into the agricultural production system, turning it into a dominant economic type. In the period of classical slavery, the commodity slave-owning estate became the dominant form of agricultural organization, but not the only one. Along with it continued to exist and occupied an important place in the general system of the economy petty production free or dependent farmers, the traditional structure of large land ownership with small land use was also preserved, especially in the provinces, for example, in Gaul, the Danube region, Asia Minor, Egypt, i.e. where the influence of the old nobility and pre-Roman traditions was strong in the era of the Empire. As far as one can see, the fate of the commodity slave-owning villa as an economic type was closely connected with the movement of the slave-owning form of private property, the evolution of classical slavery. The commodity slave-owning villa arose along with the relations of classical slavery, being their realization in main industry ancient production, and when the relations of classical slavery exhausted their internal potential, it was forced out of production by other types of farms.

What was the commodity slave-owning villa in terms of its legal, economic and organizational foundations? This is not some amorphous undivided whole, but a certain structure. The main divisions of this structure were the villa (estate) - organizational and economic center estates, then land area, on which the economy was carried out, and, finally, the equipment, which included the actual tools, animated tools (cattle) and talking tools (slaves). Only the unity of these three structural parts created economic complex and the legal status of the estate.

From the point of view of property relations, the estate was considered as the complete private property of the owner in all its structural parts. In Roman law in the middle of the 1st century. BC. developed a precise concept of private property. The full right of private ownership of living and dead inventory, as well as buildings, was established in Roman law from the time of the laws of the XII tables. However, the formation of the right to private ownership of land was hampered by the recognition of the right of supreme disposal of communal land by the collective of Roman citizens. In the post-Grakhan era, the principles of private ownership of land began to be established, and in the middle of the 1st century. BC. the transfer of the term private property to land, as it were, completed this difficult process. Since that time, the concept of private property has included the entire complex of the estate - living and dead inventory, buildings, plantings, land area as such. And one more important circumstance. The estate was considered as the complete private property of its owner personally, the master, but not of his clan, his family. Landed property in a slave-owning estate lost its tribal or family character. The estate ceased to be the property of the clan, oikos or surname, on the contrary, the surname, like the land, was considered as the property of a particular master. Characteristically, this new idea of estates as personal property was entrenched in the new principle of naming them by the names of their owners. Such an estate, being an object of full ownership, was sharply separated from other neighboring estates, not only in a legal sense, but also in a territorial one. Varro reports that the boundaries of the estate were clearly fixed on the ground either by a stone fence, or by a row of trees, or by border posts. So, the boundaries of estates in Chersonese Tauride III-II centuries. BC. (the most typical area is 25 hectares) were capital walls about 1 m high and wide. It was possible to get inside the estate through specially made gates. Such an emphasized separation of it from the environment was the realization directly on the ground of the right of private ownership of land. It should be noted that in the Roman colonies, derived according to all the rules of Roman land surveying, whether it be centuration or scamnation-strigation, in which, as is known, the colonists received plots on the rights of full private ownership, the boundaries of these plots were strictly defined or by a border strip - a road , or next to trees, or special landmarks. This system of clearly fixing the boundaries of the estate as private property emphasized its fundamental difference from the traditional allotments of citizens or early large estates, which were dominated by the sovereignty of the communal collective and family traditions.

From an economic point of view, the full legal capacity of the landowner, the separation of his estate from his neighbors, the definition of borders as roads that make it possible to connect the estate with the city without infringing on the neighbors, unleashed the owner’s economic initiative, created favorable conditions for him to organize production of any scale and varying degrees of rationalization.

What are the dimensions of a commodity slave villa? Most researchers define a commodity villa as an estate of medium size, one or two centuries (200-400 yugers = 50-100 hectares). And indeed, studying the digital material and the nature of management from the works of Roman agrarian writers, one cannot help but notice that estates of 100, 200, 240, 300 yugers are mentioned by them most often, considered as the most typical, most common. A special study of the size of the estate of Columella showed that it hardly exceeded 400-600 yugers (100-150 hectares), apparently reaching the quantitative limit for this type of farms. The figures appearing in the sources are rounded and are in a certain relationship with the basic principles of Roman land surveying, where the initial unit was a centuria of 200 yugers (there are variants of a centuria of 210 and 240 yugers). Apparently, the process of establishing a new type of economy accompanied the formation of the basic principles of the Roman classical land surveying (centuriation), which took place in the same historical period (II century BC - I century AD) and asserted the main features of this new type.

The question of the size of a commodity slave-owning estate, of the size of its economy, is not a secondary, peripheral one. Its importance lies in the fact that it leads to the problem of the optimal size of production for a given society. At each stage of the development of social production, the leading, main production cell - an enterprise, a farm, a workshop, an estate - has certain limits due to many factors: technical, economic, organizational, human, etc. The size of a commodity slave-owning villa varied between 100-500 yuger 25-125 ha), and its most frequent variant was an estate of 200-300 yugers (50-75 ha). In absolute terms, this was an average farm, differing both from the peasant allotment (apparently, a maximum of 30 yugers), on the one hand, and from huge estates, latifundia (1000 yugers and more), on the other.

Variation in size from 100 to 500 yugers, apparently, was determined by a number of local conditions: soil fertility, location, climate, degree of proximity to the city market, sources of labor replenishment.

What are the basic principles economic organization this type of farm? These can be considered: the separation of craft from agriculture, the specialization of the economy in one (or two maximum) industries, connection with the local city market and the rational organization of all production. Let us consider in more detail how these principles were implemented on the estates, and, above all, the relationship between handicraft and agricultural production proper within the estate economy. None of the Roman authors of agricultural treatises reports the presence of artisans among the slave staff, the existence of craft workshops in the villa. Varro, specifically discussing this issue, says quite unambiguously that one should not be engaged in handicraft activities in the villa, it is unprofitable to support specialist artisans, it is better to purchase the necessary handicraft products outside the estate in the city market. These recommendations are a reflection of the reality of Italy II-I centuries. BC. From Cato's treatise, one can conclude that the owner of the villa was not engaged in handicraft activities. Among the many tips that relate to even the smallest work, up to culinary, there is not one about handicrafts. On the contrary, Cato recommends buying handicrafts and names cities and craftsmen who can do it. “In Rome, buy tunics, togas, cloaks, patchwork quilts and wooden shoes. In Kalakh and Minturni - capes and iron tools - sickles, shovels, axes and typesetting harness; in Venafra, shovels; in Suess and Lucania, carts; threshing boards - in Alba and in Rome; dolia, vats, tiles - from Venafre. Roman plows are good for strong soil, Campanian plows for loose soil, Roman yokes are the best, the best plowshare is removable. Trapets in Pompeii, in Nola, under the wall of Rufra, keys with constipation - in Rome, buckets, semi-amphoras for oil, jugs for water, wine semi-amphoras and other utensils - in Capua and Nola. Good Campanian baskets from Capua. Buy belts lifting the press bar and all sorts of sparta products in Capua, Roman baskets in Suessa and Casina ... however, the best will be in Rome ”(Cat. 135). For the manufacture of special ropes, Cato recommends the craftsmen Lucius Tunnius of Casinus or Gaius Mannius of Venafre, and for this it is necessary to give them eight skins specially processed.

So, one of the fundamental principles of organizing this type of estate is the separation of crafts and handicraft activities from agriculture. At the same time, it cannot be assumed that absolutely no work of a handicraft nature was carried out on such an estate. The same Varro, who theoretically substantiated the expediency of separating agriculture and crafts, wrote: what is made of twigs and wood - baskets, baskets, tribules, winnowing machines, rakes, as well as what is woven from hemp, flax, rush, palm leaves and reeds, such as ropes, ropes, mats "(I, 22, 1). At the villa of Cato there was a forge, there was a loom, torches, props were made, ropes were woven. In the larger estate of Columella, where there was also a larger slave staff, the volume of ongoing repair and ancillary work increased, so the craft activity in general in the villa was organized; there was a weaving workshop where clothes were made for the slave administration (and clothes for ordinary slaves were bought at the market), a specialist artisan worked, and raw bricks were formed.

However, even on the estate of Columella, these were works on the repair and maintenance of the agricultural process, which were of a third-rate nature and covered only a small fraction of the extensive need for production equipment, tools and tools, which were mainly purchased in urban markets. The study of the inventory of Pompeian villas, earlier estates of Chersonese Tauride, small and medium-sized villas found in Pannonia, Dacia, Thrace, Gaul, Spain, shows how poor the set of tools that could be used for handicrafts is, and among the numerous premises of the villas there are no such , which would have been characterized by signs of a craft workshop.

Another basic principle of the local organization was the specialization of the economy in one (or two) industries. All agrarian writers, depicting the estate, do not report on agriculture in general, but first of all on viticulture, olive growing (like Cato), cattle breeding, poultry farming or arable farming (like Varro), viticulture (like Columella). Cato speaks with particular clarity about this specialization. He simply refers to the specialized estate as a vineyard or olive orchard. Columella writes about landowners who "rush about with their hay." Pompeian villas favored viticulture. Specialization depended on the need for a particular product, the abundance of labor (there were labor-intensive industries - viticulture, vegetable growing, fruit growing and less labor-intensive - arable farming, cattle breeding), soil and climatic conditions (for example, the Venafra region is unusually favorable for olives, and in the interior Etruria olive does not grow), etc.

The specialization of farms in one or two industries made it possible to make fuller use of specific conditions and to build local production in the most rational way. However, its extent and depth should not be exaggerated. According to literary data and archaeological evidence, the specialization of the estates was not deep. The vast majority of such farms, in addition to one, the leading industry, had others. In addition to vineyards, Cato's estate had a grain field, an olive orchard, a meadow, a vegetable garden, a forest, herds of cattle, etc. In the olive garden of Cato, a vineyard is laid out, bread is sown, herds of cattle roam, a meadow and a vegetable garden are cultivated. A similar picture is in the estates of grain, livestock or meadow direction. From the remains of rural villas, for example, in the vicinity of Pompeii, many services can be identified that provided various industries: storage for wine and oil, barns for grain, haylofts, stalls, wine and oil presses. In such a villa, in such an estate, all branches of agriculture were represented, naturally, as far as the soil and climatic conditions allowed (in a number of regions of Northern Italy, for example, olives do not grow, stony soil is not suitable for grain crops in Tauric Chersonese, etc.) . Thus, the specialization of estates in one industry did not imply the absence of others and did not turn into a monoculture: one industry became the leading, main one, while maintaining a multi-industry basis. The choice of the main industry was determined by specific natural and economic circumstances. The presence of many agricultural industries in such farms made it possible to provide the working staff of the estate and the city house of its owner with their own products, without resorting to the services of the market, and thereby ensured autarky and self-sufficiency of the entire economy as a whole. The leading industry, which stood out sharply in its specific gravity and the volume of the harvest, was specifically market-oriented, providing the master with cash receipts for purchase through the market for handicrafts. We can talk about incomplete and shallow specialization, about a peculiar combination of natural and commodity principles in the organization of farms of this type: most of the products received were distributed directly in the slave owner's oikos, a smaller part acquired a marketable appearance.

Product specialization at natural basis on estates of this type predetermined the appropriate level of agricultural technology and the production process as a whole, and one can speak of a certain duality in the approach to the organization of production. The presence of a leading market-oriented industry (vine growing, olive growing, etc.) posed a number of tasks for the owner: in order to obtain more income in the market, he had to supply competitive products there, i.e. High Quality. There was no point in bringing bad goods to market. And in order to obtain high-quality products, it was necessary to apply high agricultural technology, advanced (for that time) technology, the best tools, and use skilled labor. Roman agricultural writers gave a very detailed exposition of ancient agricultural technology. She had a very high level in these farms. It is curious that the author, a supporter of one or another specialization of the estate, gives the most detailed description agricultural technology of the corresponding culture. Thus, Cato states best recommendations on olive orchard care (lists the best varieties, most favorable soils, writes about pruning techniques, establishing a nursery, improving breeds using grafting, etc.), Varro owns the best and most detailed manuals on stall and distant pastoralism (among various tips Varro even has recommendations for caring for livestock, which wives should be selected for shepherds and which breeds of dogs), as well as home poultry farming.

None of the ancient authors gave such an exhaustive description, a real encyclopedia of viticulture, as Columella (as many as three books), whose advice was valid throughout the Middle Ages and at the beginning of the new time, and to this day amaze with its completeness and content.

Agrotechnics in a commodity slave-owning villa of the 2nd c. BC. - I century. AD had a very high level in general and the highest within antiquity. Let us note only three features of Roman agriculture that testify to its high level: restoration of soil fertility (fertilization of fields), the introduction of proper crop rotations, an increase in the variety of main crops through the acclimatization of foreign plants and through our own breeding work. The Romans mastered almost all types organic fertilizers, including green manure and soil horizon, and even some mineral (for example, in Gaul marl - Plin. XVIII. 42-48), found in a particular area in finished form. Columella's recommendations on the use of different types of fertilizers for different soils, their preparation and storage, and the norms of use were not only the result of purely practical observations, but were comprehended from the point of view of a special concept of soil fertility. The system of restoring soil fertility by fertilizing fields, as formulated by Columella and Pliny the Elder in the middle of the 1st century BC. AD, remained virtually unchanged in Europe until the start of use chemical fertilizers in the 19th century

The outstanding achievement of the Romans in agriculture was the understanding of the role of crop rotation as an important factor in increasing yields. Complex crop rotations were developed and put into practice, providing for a multi-field (usually four-field) alternation of crops, elements of fruit rotation and a grass-field farming system. Columella's remarkable idea that proper cultivation of the land, involving thoughtful cultivation of fields and skillful alternation of crops in skillfully chosen crop rotations, would ensure an increase (and not exhaustion, as many ancient agronomists believed) of soil fertility, reflected the practical experience of commodity slave-owning villas.

The problem of using this type of equipment, agricultural implements on farms is somewhat more difficult for researchers. In historiography, both domestic and foreign, for a long time the point of view about the low level of ancient technology, including agricultural implements, dominated, since under the dominance of slave labor there were no incentives to improve it. First of all, on what are judgments about the low level of ancient agricultural technology based? Usually, researchers proceed from its comparison with the achievements of the 19th-20th centuries. But this approach is hardly correct. It will be more reliable to compare the ancient level of agricultural technology with the previous one, namely with the level of technology of the ancient Eastern countries, the Greek policies, the Hellenistic era. It will show significant progress. Not to mention the invention of the wheeled plow, which apparently received very limited use, the moldboardless plow of the time of Varro and Columella was not primitive, but provided high-quality (for that time) plowing. Recent discoveries images of reaping machines in Belgium, special studies of individual agricultural implements (harrows, winnowing shovel, etc.) show a certain shift (from our point of view, quite significant) in this area of agriculture, although slave labor itself did not contribute to the overall technical progress .

In what farms were all these achievements applied: on peasant plots, in the open spaces of latifundia? Our sources, and above all the writings of Roman agrarian writers, quite definitely associate them with commodity slave-owning villas. The leading, main, commodity branch of the specialized estate was organized according to the latest agricultural technology of that time.

Since the products of other industries did not go to the market, they did not face such an acute problem of quality, and, consequently, the use of advanced agricultural technology, which required large expenditures and the use of skilled labor. That is why Columella, this brilliant agronomist and zealous owner, who received fabulous yields of vineyards, speaks directly about the unprofitability of grain, ridicules those who "rush around with their hay and vegetables." At the same time, Varro emphasizes the high profitability of livestock and poultry farming and is reserved about other industries (for example, olive growing). We would be making a mistake if, following Columella, we began to talk about the crisis of the grain industry in the 1st century BC. AD or following Varro - about the decline of olive growing in Italy in the 1st century. BC. Research evidence suggests that this was far from the case.

It's about that the commercial advanced industry on the estate of Columella was viticulture, and in the possessions of Varro - animal husbandry, while the rest of the industries were only maintained at an average, usual level: less fertilizer was applied, and care was less thorough, and plowing was not three times, but two times and the workers were low-skilled. Thus, in the same economy, there was advanced technology and traditional methods, i.e. the dual nature of agricultural technology was observed, associated with the peculiarity of specialization, the selection of one commercial crop from all others.

In general, the commodity slave-owning villa, despite the deep dualism of its structure, acted as the most advanced economy for that time, the face of which was determined by the main, leading industry. It was here that they received the largest harvests, the most abundant collections. We have very little accurate data on the yield of different crops at our disposal, but these few data are very characteristic. Thus, Columella reports that he received 10 skins of wine (i.e. 200 amphoras) from the yuger, using advanced technology, but he also speaks of yields of 3 and even 1 skins within the framework of traditional agricultural technology (Col. III. 3. 7-11). Barron gives data on the yield of cereals for most of Italy itself-ten and for Etruria itself-fifteen (about 17-25 centners per hectare). And Columella says that in his time, the grain yield in Italy did not exceed sam-three, sam-four, i.e. was 3-4 times smaller. (However) Columella's data do not reflect the real situation with cereals in his time. In our opinion, he had in mind the culture of cereals on the estate, where the leading industry was viticulture (as, apparently, on his estates) or some other. Varro's data refers to estates where grain was cultivated for the market on the basis of advanced agricultural technology. The contrast between the yield of commercial crops and non-commodity crops is very large. The absolute values of the yield of vineyards at Columella or cereals at Varro indicate high efficiency advanced technologies.

The described type of farming is defined by us as a commercial villa, since in the very structure of the estate, the culture oriented to sale stood out sharply in terms of its share. In general, the connections of this estate with the market were the basis of its economy, determined its internal structure. The rupture of these ties led to a radical restructuring of the economy, changing its very type and structure. Indeed, almost all products of the leading industry (and surpluses of the rest) were exported to the market, handicrafts, clothing, most of the inventory, work force. On the other hand, the growing cities of Italy, and then the provinces of the Empire (especially in its western part), the growing urban population needed all foodstuffs: bread, wine, butter, meat, vegetables. A study of one of the small Italian cities that was Pompeii shows that in its streets and shops there was a brisk trade in a variety of products: raisins, grapes, wine, oil, olives, wheat, barley, beans, vegetables, meat and many others.

The commodity estate was connected with the city market in a variety of ways, of which the main ones were three: 1) the production of a product in the villa (for example, the preparation of wine, oil) and its export to the neighboring city to the market, where it was sold; 2) preparation of the product in the villa and its sale here in the villa to the buyer, who then transported the product to the city market on his own; 3) selling the standing crop to a buyer who, on his own, harvested the crop, prepared the product, transported it to the city and sold it on the market. Apparently, the predominance of each of these three forms was determined by the local economic situation: the need of the urban population for products, crop yields, price fluctuations, and the state of the road network. Perhaps one should not underestimate the significance and prevalence of the last two forms of commercial relations of the estate (the sale of a finished product or harvest on the estate itself to the city dealer). These forms were already well known to Cato, they are very convenient from an economic point of view for the landowner. Indeed, for the independent sale of their products in the city market, usually separated by several tens of kilometers from the estate, additional transport and staff of merchants were required. Apparently, it is no coincidence that Roman agrarian writers report almost nothing about any additional funds allocated by the owners of estates to service their own trading operations. At the same time, they especially emphasize the need to establish trade relations and unanimously recommend setting up farms near a busy road or on the banks of a navigable river. As you know, the Romans paid close attention to the condition of the road network. Even if we leave aside the famous Roman roads of imperial significance, which had not only military and administrative functions, but also commercial ones, in every region, in every municipality, an extensive road network was created that connected literally every estate with a local city or regional center. A striking example is the system of Roman centuriation, which legally considered all boundaries, from the boundaries of the smallest plots to the main planning axes, as roads, so that the territory of the colony was covered with a dense web of roads of various kinds.

Trade relations between commodity estates and cities were also facilitated by the improvement monetary circulation, which reached a special intensity precisely during the heyday of this type of commodity villas. Emphasizing the importance of commodity relations between the estate and the city, their well-known scope in the 2nd century. BC. - II century. AD, one should not, however, exaggerate them, overestimate their importance in the general system of the economy. After all, there were also economic types with natural production ( peasant farms, latifundia with small land use), whose products were rarely released to the market. In addition, in the very structure of commodity villas, a significant part (at least half) was occupied by non-commodity industries. And one more circumstance. Regular commercial relations of this type of estate were established only with the neighboring nearest city, relations with other centers were only sporadic and played a purely auxiliary role. Campanian amphorae with wine and oil were found in the cargo of a ship that sank off the island of Grand Conluet near Massilia; they were discovered during excavations on the Istrian peninsula and in a number of other Roman provinces (in Gaul, Spain, the distant cities only an insignificant part of the total agricultural production was exported.

The structure of production in the commodity estate bore obvious features of a rational organization, subordination to the action of economic laws, pursued the goals of self-sufficiency of the master's oikos, on the one hand, which was used for at least half of the output, and making a profit in monetary terms, on the other hand, since the other half of the output taken to the market. With such an orientation of the economy, naturally, the problem of its profitability, the degree of its profitability, arose. She stands at the center of attention of all Roman agricultural writers, from Cato to Columella and Pliny. In fact, their extensive treatises are written to solve the problem of the profitability of the estate. We have two calculations at our disposal, which allow us to more accurately represent the profitability of a commercial villa. So, Varro reports that the death of a skilled craftsman takes away the annual income of the entire estate. A skilled craftsman-slave cost on average about 20-30 thousand sesterces. This is the estimated income figure; however, we do not know the size of this estate. In another place, Varro says that the estate of Senator Axius in Sabinia with an area of 200 yugers brings 30 thousand sesterces (i.e. 150 sesterces per yuger). If we consider that one yuger cost 2000-3000 sesterces, then the yield of the estate was about 6% - approximately as much as the usurious interest on capital gave. In the 3rd book of Columella, a detailed calculation of the profitability of vineyards is given, which he considers to be the most profitable crop. According to the author's own calculations, this yield reached 34%. However, a careful analysis of his calculations showed that Columella did not take into account many expenditure items. This reduced the yield figure to 7-10%, and yet it exceeds Varro's data by 1.5-2 times. A yield of 5-10% made it possible to recover the cost of capital expended over 10-20 years. In other words, the owner of an estate of 200 yugers could earn 30-60 thousand sesterces a year, which should be recognized as a high profitability, allowing him to accumulate half a million fortune in 10-20 years.